-

- << >>

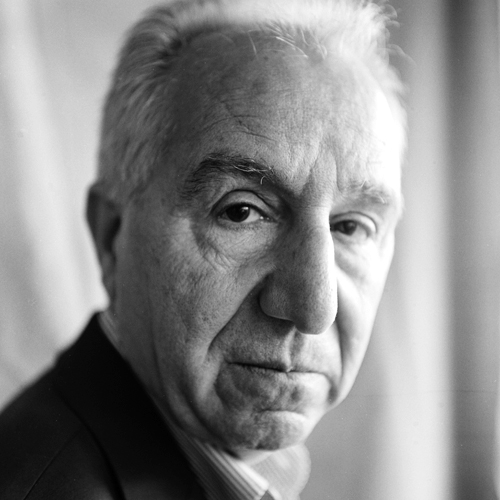

Parviz Dastmalchi, survivor (and later trial witness) of the Mykonos assassination.

On 17 September 1992, contract killers murdered three Kurdish-Iranian politicians and their friend and translator in the Mykonos restaurant in Berlin on behalf of the Iranian state leadership.

Parviz Dastmalchi has a Master's degree in political science and is a translator and the author of numerous books and articles in Farsi on Iranian state terrorism and the construction of the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI). For almost 20 years, he was responsible for the management of a refugee shelter in Berlin.

What do you remember first when you think of your childhood in Iran?

Parviz Dastmalchi: I did not grow up in affluent circumstances and had a difficult childhood and youth. I lost my father when I was three years old.

Perhaps one can imagine how difficult it was under Iranian conditions to grow up and struggle through life back then. When I am with my grandchild, whether at my home, in the playground or at the zoo, I think a lot about my childhood and compare it with my grandchild's childhood; they are two totally different worlds.

What was the importance of religion in your family?

P.D.: We were not a religious family, unlike the area of Tehran where I grew up in. The rich lived in the north of Tehran, the very poor in the south, and we lived roughly in between, but much more towards the south. My father was a descendant of a Bakhtiari tribe and traditionally religion played no important role there.

My mother was also not a religious person at all, but the family and all my mother's relatives were very strictly religious. So in my family, religion didn't play a big role and none of us, for example, prayed every day or fasted during the month of Ramadan.

How did you experience the 50s and 60s in Iran as a child?

P.D.: It was a time of awakening to modernity.

We noticed that everything was changing in a positive direction, e.g. the radio was very new and there was still no television. When I was seven or eight years old, I heard rumors from other children and adults that soon a new version of the radio would come out where you could see the speakers. I wondered about this as a child and it was incomprehensible to me how such a big speaker could fit into such a small box. How was it possible for the speaker to be heard and seen both by us and everyone else at the same time?

So it's all nonsense, I thought to myself, it's impossible and not logical, until this miracle box, the miracle radio, that is television came along.

We also heard at that time that a big department store was opening in Tehran: The Ferdowsi department store in the centre of Tehran, where the stairs simply roll up and down. I thought again, it's all nonsense, how can these stony stairs, which are walled in, just roll up and down; it all collapses, it's impossible. But we heard from all sides that there really was such a thing. Once I walked with two friends to this department store, about ten kilometers from home, because we really wanted to get inside to see this marvel of technology. When we got there, there were many other curious people besides us. Guards stood in front of the entrances to the department store. We told a guard that we only want to see the escalators. We were refused entry because we were not accompanied by our parents. We then said that we wanted to buy ice cream, but we only had money for one ice cream. So only one of us was allowed in and he was told to come out immediately. I then went with the other friend to another entrance and we just secretly joined a family with lots of children and finally got into the department store. We were absolutely thrilled with this marvel of technology. We rode up and down the escalators in the department store until a guard spotted us, chased us and beat us and threw us out of the shop.

For us children, that was our first encounter with the new world and the new technology. For our parents, it all seemed completely new and strange, too.

Did you take part in the protests against the Shah and if so, why?

P.D.: Yes, we thought we could create a better world that way. Very naïve from today's point of view; I was 27 at the time and today I am 72 years old. We had no idea of the danger of Islamism.

At high school, I belonged to a group of diligent students who were also known for reading a lot, including critical novels. At that age, as a teenager with no experience or knowledge, everything I did was very emotional. I was concerned with the unjust social conditions and the prevailing poverty in Iran, which was due to historical reasons. But as a teenager, of course, you had no overview and no understanding of the historical background.

For example, I heard at the time that in the neighboring country of the former Soviet Union, society and production were organized in such a way that there were factories for the production of bicycles and so many bicycles were produced until every Soviet citizen owned a bicycle. Then radios are produced and everyone gets a radio. And after the radio there are motorbikes and so on, and we thought this is a fair society. Everyone gets what they need.

Or we were told that music in the Soviet Union was supposedly so developed and advanced because every family there had a piano at home. That was unimaginable for us, because only very rich people could afford a piano in our country. We thought everything was totally good and were enthusiastic about it.

Of course, it was all just propaganda and we had no way of finding out for ourselves whether it was true or not. For these reasons, we were very critical of the Iranian system at the time. With this background and these ideas, I travelled by bus (Tehran - Munich) and train (Munich - Berlin) to Berlin in 1970 to study, because I had heard that you could study for free in Germany and at the same time earn the necessary money for your own life through work. In Berlin, I joined the Iranian student movement (CISNU).

When and why did you leave Iran?

P.D.: I left Iran for the first time in 1970. In 1974 I flew to Iran to marry my wife, whom I met in Germany. My passport was confiscated at Tehran's Mehrabad Airport and I was given an address where I should report after two weeks, which I did. It was an office of the then Iranian secret service SAVAK. On my third or fourth visit, I was arrested and taken directly to Ghezel Ghaleh prison and locked up in a solitary cell. I was told that the reason for my detention was my »harmful activities against national security abroad«. I was released after three months, but was banned from traveling abroad. Almost half a year after my visit to Iran, I was able to return to Germany.

During the Iranian Revolution, which eventually led to the Islamists coming to power, Shapour Bakhtiar was appointed Prime Minister in early 1979 and the names of politically persecuted people were removed from the intelligence service lists working at the borders. My name had been on this list, so I could enter and leave the country freely again. I went back to Tehran. The Shah was still there. It took another month, the uprisings against the Shah continued even more intensively and now included almost all layers of the society. The Shah had to leave the country with the hope of returning at some point when everything had calmed down and normalized. It was all too late.

Back then, after my entry, I had to realize immediately that things in Iran had taken a different course and did not correspond at all to my ideas of democracy, freedom and human rights. The fundamentalists had the upper hand almost everywhere, there was an unimaginable dimension of violence and brutality, which was justified by the necessities of a revolution. Everything was going in the wrong direction.

For example, thousands of veiled women at demonstrations carried a poster showing the Iranian empress Farah Diba on the beach in a swimming costume and they shouted, that is the evidence for the crimes committed by the Pahlavi dynasty. I thought, that's not a crime after all, and I saw Islamic fundamentalism rising up.

It had nothing to do with democracy, human rights and our ideals. Soon there came a moment, when I realized that I had neither money, nor shelter or anything or a job to earn the money I needed to live. I decided to return to Germany as soon as possible and graduate with a degree in political science. My idea was to apply for a teaching position as a lecturer at Tehran University with this title. I completed my studies in Berlin with a diploma and at the same time continued my political activities, but now against the new rulers, against the Islamists and against Chomeini's state of God.

I gave lectures to the Iranian student organizations about the new Iranian form of government Welāyat-e Faqih, the ›rule of the jurists‹. I argued why a religious-green ›fascism‹ had now taken over in Iran. Back then it was very daring and risky to say something like that openly in front of Iranians, as many were totally enthusiastic about Chomeini and politically supported him and the mullahs. When I went to the Iranian consulate in Berlin in 1980 to renew my passport to go to Iran, it was confiscated on the grounds that I was a counter-revolutionary. And for that reason I had to ask for political asylum here in Germany and stay. Almost 41 years have passed since then.

What irritated you most when you arrived in Germany?

P.D.: The first time I arrived in Berlin was in autumn 1970 with a friend by train. That is, from Tehran to Munich by coach and then from there to Berlin by train. In Berlin we got off and waited on the platform for my friend's brother to pick us up. But he did not come. We waited for almost half an hour. He didn't come and we decided to leave the platform, walk out of the station and call him. Outside the station he greeted us and we told him that we had been waiting on the platform for about half an hour and why he had not picked us up from the platform. He said it would cost 20 penny, he didn't have that much money. He was a student himself and had very little money to finance his life. He delivered newspapers every morning for 230 D-mark a month. Then we went with him to a completely run-down flat with an outside toilet in Kreuzberg, which didn't correspond at all to my image of Europe.

Now many years have passed and I am happy to live in Germany. I have very good German friends. My daughter is an actress and director at the Deutsches Theater and I have a great grandchild.

Why did Iranian contract killers murder four Kurdish-Iranian politicians in exile in the Mykonos restaurant in Berlin on 17.09.1992? Should anyone else be killed in this incident?

P.D.: The documents and the court case have shown that exactly these four people had to be killed. Three of those killed belonged to the leadership of the Democratic Kurdish Party of Iran and the fourth was a very close friend of leaders of the Democratic Kurdish Party. The leadership of the Islamic Republic of Iran had different reasons for this contract killing: the Kurds are followers of the Sunni faith of Islam, while the rulers are Shiite. The Kurds are fighting for a democratic Iran. The influence of the party in Kurdistan is very great and it strives for self-administration of Kurdistan in Iran. This was a thorn in the eyes of the Iranian rulers.

In the Mykonos trial, the German government tried to influence the course of the trial because of the close economic ties to Iran, in order to avoid as far as possible the impression that it was a state contract killing. However, the federal prosecutors were so courageous and sovereign that they clearly pointed out in the verdict who was behind the murders, e.g. the Iranian religious leader Khamenei. Has the economic relationship between Germany and Iran changed as a result of the verdict in the Mykonos trial?

P.D.: In the short term yes, in the long term no.

After Trump came to power in the USA, the economic relationship with Iran changed again due to the sanctions. However, Europe and especially Germany had no great interest in a confrontation with Iran, also because of the billions in economic business deals.

While the economic relations between Iran and the USA, England or Israel ended with the Islamic Revolution, Germany tried to gain a foothold there after 1979 and to fill the vacuum that had arisen. With the help of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Europe and Germany wanted to establish a policy in the Middle East that was independent of the United States. That is why the German government had no interest in the Mykonos trial to make the people behind these murders public.

For example, three weeks after the Mykonos assassination, the official story was that the perpetrators had left Germany. This was perhaps an attempt to take this story out of the headlines. It was the British secret service that informed the German intelligence services that the perpetrators were still in Germany and they were also able to provide the perpetrators' home address.

Are there any questions about the Mykonos attack that you are still looking for answers to today?

P.D.: Yes, the question about the traitor(s).

Do you feel safe in Germany?

P.D.: Yes, I feel safe. I have dual citizenship. It's a big risk for the rulers in Tehran to commission the killing of a German citizen in Germany.

When, after the verdict in the Mykonos trial, some European countries (including Germany) closed their representations in Iran in protest against the state terrorism of the IRI and recalled their ambassadors, the rulers in Tehran came under very great pressure. Later, some politicians in Berlin told me that IRI had promised them not to carry out any more terrorist acts in the European Union, and they kept this promise until three years ago.

About three years ago, they started again to eliminate opposition members or whoever they consider as their opponents abroad. Each time they hope not to be discovered. They have changed their tactics by hiring criminal gangs to do the killing instead of using their own people.

The attack in Berlin was about 28 years ago. I was an eyewitness to four brutal murders at that time. I experienced with my own skin how brutally and ruthlessly this regime dealt with dissidents. The danger was real and very great. It was a very difficult situation for me. You always had to expect to be the target of an act of revenge. Even before the four murder in Berlin, three Iranian celebrities had been killed abroad within a year, namely Shapour Bakhtiar and his deputy in Paris and Fereydoun Farrokhzad near Cologne. After the assassination in Berlin until the sentencing in April 1997, other Iranian dissidents were murdered in various European countries (Italy, France).

We are dealing with a regime where state terrorism is inherent in the system and part of the ruling apparatus. Back then, I had to leave my flat every day at seven o'clock and go to work. After closing my flat door, I thought someone was waiting for me during every step walking down the stairs. The experience of the murder had logged itself into my subconscious and kept coming up automatically. It's like this: You get in your car, you start it and automatically the thought comes, now the car is going to explode. At every intersection, if there's a car or motorcyclist next to you, you think, it's over. You are sitting in your office and a stranger comes up to you and you think it's over.

One day I said to myself, I can't go on like this, I can't go on living like this. By chance I read in a magazine that the average life expectancy in Africa is 40 years. Then I said to myself, Parviz man, you are over 40 now, what more do you want. Because of this relativization of life and the change in my attitude towards life, it was much easier for me to deal with the consequences of the attack.

Thousands of people have had to pay with their lives to this day for the struggle for freedom and democracy and against the rulers of the IRI's God-State. We are dealing with a very brutal, totalitarian, religious regime, similar to IS.

Already 40 years before the Islamic Revolution, the Iranian intellectual Ahmad Kasravi warned against the Shiite clergy in politics and was murdered by Islamists for this reason.

In 1963, Chomeini strictly rejected the modernization of women's suffrage in the wake of Shah Reza Pahlavi's White Revolution, and his contempt for Western, parliamentary democracy and his hatred of the USA and Israel were no secret. At the same time, before the Islamic Revolution, the political left made itself a stooge of the Islamists inside and outside Iran, even though leftists themselves were among the victims of Islamist terror after the revolution. Has the political left learned anything from Iranian history?

P.D.: A part of the left has learned something. The anti-Western attitude of the left, which was linked to the idea of socialism and anti-imperialism, simply did not see what a reactionary force was taking over almost the whole of Iran in the name of the revolution led by Chomeini. Many leftists said they supported Chomeini and the Islamists because Chomeini promised good things in Paris, such as women could live as they wanted or communists could even go into the parliament.

If you knew Chomeini, his ideas and thoughts a little bit, you knew immediately that everything he said was just lies and nonsense. If you really want to take someone seriously, you can't just refer to what he claimed within the last two months in Paris, because Chomeini had a past and a history. He almost always ended everything he said with the final sentence »... but within the framework of Islam and Sharia.«

We had Chomeini's uprising in 1962 against the positive changes and reforms, e.g. active and passive suffrage for women or the land reforms in favor of the peasants, where the feudal lords and big landowners were disempowered. We had forgotten that the clergy in Iran was overthrown by reforms of Reza Shah (the father of the Shah).

He took the judiciary, which in Iranian history until then had been in the hands of the mullahs and was only administering law in accordance with Sharia law, away from the clergy and replaced it with a modern judiciary. For the first time, women in Iran had the right to go to school and to take off the veil. And Reza Shah founded a modern school and university system. Previously, the school and education system was in the hands of the clergy and ran only according to Sharia law.

Because of his reforms, Reza Shah basically did in part to the clergy in Iran what the French Revolution had done to the Church: a disempowerment.

But the Iranian intellectuals did not appreciate this properly and this was a huge mistake. The hatred against the West, against imperialism and capitalism and the sympathy for a Soviet, Albanian or Chinese socialism have led to the fact that one has become totally blind. Iranian leftists were either pro-Soviet, pro-Chinese, pro-Cuban or pro-Albanian at that time. These states were neither democratic nor organized on the basis of human or fundamental rights. There was a dictatorship everywhere. The Iranian-Islamist revolution was a reactionary revolution. The mistake of the left can still be seen today in the war between Hamas and Israel, they still sympathize with Hamas.

What is the most important thing you have learned from the Islamic Revolution?

P.D.: I learned that the Islamist fundamentalist movement, which was misjudged by almost all of us and is still misjudged by a part of us today, is a historical, reactionary movement against modernism; it is quite simply reactionary.

There is a memorial plaque for the victims of the Mykonos-assassination at the former crime scene in Prager Straße in Berlin. The plaque names as the perpetrators the rulers of Iran at the time, which to this day is still the religious leader Ali Khamenei in the first place.

Today I understand much better and know that this fundamentalist, reactionary movement was not a direct reaction to the Shah's policies. When you realize that this movement has spread all over the Middle East and from North Africa to the middle of the African continent, then there had to be another reason than the Shah's policies. If this fundamentalist movement had only been a reaction to the Shah's policies, then it would have been limited to Iran.

It is a historically reactionary movement against the Enlightenment and a modern society and against modern people who want to decide for themselves about life and politics.

To this day, it is claimed that the overthrow of Prime Minister Mossadegh by British intelligence and the CIA in 1953 was the cause of the entire further development of Iran.

Is this claim justified?

P.D.: This claim is false and not justified. Of course, the coup was a mistake and an interference in Iranian affairs, but the fundamentalist Islamist movement in Iran had developed long before Mossadegh came to power. This claim is too hypothetical and a political assessment without proof.

Before he went into exile in 1979 Shah Reza Pahlavi had instructed his Prime Minister Shapour Bakhtiar that the Iranian military should not fire on its own population. Exactly 30 years later - in 2009 - the Iranian regime reacted the other way around on the occasion of mass demonstrations (Green Movement) because of electoral fraud: instead of asking for a vote of confidence, security forces put down the protests with brutal force, numerous people were killed and thousands of Iranians arrested. Thousands of Iranians were again killed by security forces during nationwide demonstrations in Iran in late 2019. Can the Islamic Republic of Iran reform itself from within?

P.D.: I don't think so. It is an ideological, fundamentalist system, comparable to the former Soviet Union or countries in Eastern Europe.

Any serious reform within this system, political or economic, will lead to the collapse of the system. If the system really could be reformed, the rulers would have done so long ago out of their own interest.

Take, for example, just one article of human rights, namely the equality of all people before the law. Assuming, this article were actually implemented in Iran, then the entire system of rule of the legal scholars would collapse. If the religious leaders, the council of guards or the council of experts were not only mullahs or Islamists chosen among themselves, but everyone, men or women, Muslims as well as non-Muslims, etc. who are elected by the people, then the whole system collapses. For the same reason, elections in IRI can never be democratic, free and fair.

Women are excluded from almost all constitutional organs in Iran by constitution and law, which means that equality between women and men is out of the question for those in power. Equality of all people before the law is against the Sharia, i.e. against God's law.

The Islamists see women as inferior beings, it's as simple as that.

With the IRI, we are dealing with a state system that has developed from the Islamic Shiite faith of the 12-Imamites and from the school of Welāyat-e Faqih, i.e. the rule of the jurists. This system cannot be reformed any more than, for example, the system of the Khmer Rouge under Pol Pot in Cambodia or the IS and the Taliban. We are dealing with a new form of totalitarianism, a state of God. It's the IS, but a Shiite version.

Western media distinguish between moderates and hardliners in Iranian politics. At the same time, the ›moderate‹ President Hassan Rouhani said: »Surrender is not compatible with our mentality and religion«. Since Iran's rulers, who have lost the trust of the majority of the population long ago, have so far sidelined, imprisoned or killed all critics of the system in Iran, is it not to be feared in this context that they will drag the whole country into the abyss rather than resign like the Shah?

P.D.: Iran has already been dragged into the abyss by the rulers of the IRI.

Iran is a rich country and it could have been developed very well in the last 42 years with a democratic and popularly elected government. But this is not possible with this state of God, because the two wings - moderates and hardliners - want to have an Islamic religious state based on Sharia law. It doesn't matter whether a person is denied his basic rights in the name of the hardliners or the moderates.

In Iran, we are dealing with a kind of Taliban or IS. The history of the last hundred years shows that totalitarian systems cannot be reformed. The ideology of the Islamists is a life-denying one and knows no differences between ›moderates‹ and hardliners. They live for the hereafter, with their martyrdom they want to go to paradise, to the virgins — all complete nonsense and insane.

Before 1979, Ruhollah Chomeini incited the Iranian population against the Shah with speeches on audio cassettes from his exile in France. Today - 40 years later - the Iranian state broadcaster IRIB (Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting) is broadcasting its propaganda to the world via the French satellite Eutelsat. Is Western Europe naive, ignorant or just indifferent towards political Islam?

P.D.: I would say naive in the sense that one thought in Western Europe that with a rapproachment to and support of the Islamists in Iran one could achieve control of the hardliners.

But this is mistaken, because these people, who also live in the West, see the West as a false, corrupt society and they want to change everything, including in the West, according to their Islamic model of the IRI. This is the wrong policy. You have to educate and control them at the same time.

Many of the so-called Islamist ›welfare‹ organizations, such as Hezbollah, which allegedly raise money for children in the West, are part of this large Islamist movement. And the money donated serves Islamist purposes and goals that are incompatible with the values of a democratic, open society.

What is the importance of the People's Mujahedin for Iran, who on the one hand was listed by the European Council as a terrorist organization from 2001-2009 and on the other hand has good contacts with Western politicians?

P.D.: The People's Mujahedin play a major role for Iran and those in power are afraid of this organization. The People's Mujahedin are very well organized. They have their cadres, they have over 60 years of ›fighting‹ experience, they speak the national languages of Iran and they know the culture very well.

They are not popular among a large part of Iranians and this is related to their former policy and rapprochement with Saddam Hussein. The People's Mujahedin is one of the most strictly organized political associations. If there were a peaceful transition in Iran through elections, I don't think they would play a big role. They will be able to send a few deputies to parliament. But if there are armed conflicts with the rulers, then they might have a chance because they have the necessary military means and experience.

Today, the People's Mujahedin claim to be fighting for a democratic society, but the Iranians are very skeptical and do not trust them.

40 years of the Islamic Republic of Iran have not led to the people of Iran being particularly religious, but the violence and false promises of the spiritual, political leaders have transformed Iran into one of the most secular countries in the Middle East today. Against this background, which values can form a basis for a new constitution in Iran?

P.D.: The Iranians have experienced different things. First the dictatorship of the Shah, which at the time was not a totalitarian system, but a modern, reformable state. Then came Ayatollah Chomeini with his Islamist ideas of an ideal society based on Sharia, a state of God.

In fact, the people have experienced something in the last 42 years that might take a period of 200-300 years for an Enlightenment. The common people have seen and experienced what the Islamic values mean in practice, for example, for women, children or girls, who can be married from the age of 9. It's rape of the children.

As far as the values of human and fundamental rights, popular sovereignty and a modern form of government are concerned, we have been thrown back into the Middle Ages. The very fact that this system, even after 42 years, can only stay in power with state repression and brutal violence, means that it is not viable. The state of God is simply not capable of solving its own fundamental contradictions and problems. These contradictions will eventually lead to the collapse of the system, as in Eastern European countries or the former Soviet Union.

I'm convinced that this collapse will happen, sooner or later. A new constitution must be built on the values of democracy and human rights. Personally, I'm in favour of a parliamentary democracy. History over the last hundred years shows us that there is no better form of state and society.

What is the most effective and responsible way for the West to support civil society and human rights in Iran?

P.D.: There must be constant political and economic pressure on those in power in Iran and there must be no false concessions. Compliance with human and fundamental rights must be demanded again and again. The Iranian people will do the rest.

The uprisings in Iran in 2017 and 2019 in more than a hundred cities within three days show that Iranians are on the one hand very well organized and on the other hand how great the dissatisfaction is among the population. According to human rights organizations, over 1500 people were killed and thousands arrested in these protests. My information from reliable sources in Iran says that the number of people killed is exactly 2271. Those in power can only hold out by force and they delay the necessary changes. But these will come, sooner or later.

The West should stand behind the Iranian people and their demands for human rights and self-determination and not flirt with the rulers of the IRI.

In which areas or at which levels should the West cooperate with Iran and where definitely not?

P.D.: IRI pursues the goal of establishing a uniform Shiite Islamic society and a state based on the example of Iran in the region and around the world. This goal must be stopped at all costs, as it is a great danger for Iran, the region and the whole world.

Help could be offered in projects such as water supply, the construction of desalination plants or even in education, as it benefits the population. But whatever is done there, the improvement of the human rights situation must not be forgotten.

The West should support independent civil societies, women's organizations, trade unions as well as human rights organizations. Lifting the ban on demonstrations and allowing the formation of political parties could be very useful. Democratic, free and fair elections without interference and candidate selection by the Council of Guardians could facilitate the transition to democratic conditions.

What is the most valuable thing for you, that you preserved from your Iranian past into exile?

P.D.: The most valuable thing for me is my solidarity with the Iranian society and that, despite the pressure from Tehran, I did not give in and continued my work for human rights and democracy in Iran.

After the Mykonos assassination, I devoted many years of my life to investigating the state terrorism of the IRI, with the hope that I might be able to save a few lives. We must not forget that we are all human beings and when we are born, we have no religion or nationality or anything, but are only human beings.

You have spent more than half of your life in exile. Do you still feel homesick for Iran?

P.D.: Yes, there is always homesickness, but I have to be realistic. As long as this state of God exists, there is no going back for me. I have to continue with my political and educational work until the conditions there have changed in a positive way and then I can visit the country again and maybe stay there forever.

Although I really enjoy living here in Germany, I have many very good German friends and have learned a lot from this society here.

Assuming you could go back to Iran, where would you go first?

P.D.: First, I would go to Tehran and if there was the possibility, I would continue to get involved in the countries politics and accept my responsibility there. If not, my wife and I would rent a car and travel all over the country to really get to know it, which I unfortunately didn't do before.

06 / 2021

<< >>