-

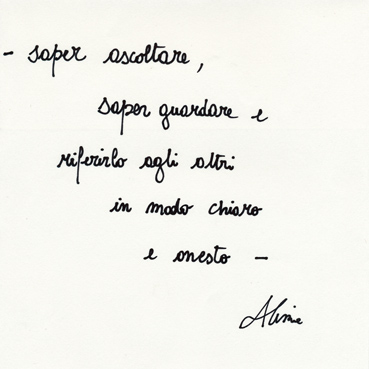

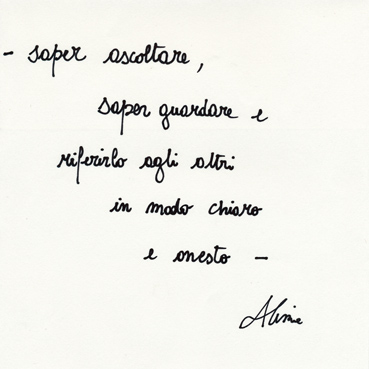

- »Listening, watching and reporting it to the others in a clear and honest way.«

Alessia Cerantola (co-founder of IRPI) about the sense of journalism

What is IRPI?

Alessia: IRPI (Investigative Reporting Project Italy) was officially launched in Rome in July 2012 and so far it is unique in Italy.

Some of us previously met at various conferences and were impressed by similar organizations abroad, eg ICIJ in the United States. So we asked ourselves why we couldn't start something similar in Italy.

In the beginning IRPI consisted of 7–8 people, plus co-members and external supporters. IRPI also includes a network, so anyone, who wants to contact us or has suggestions has the possibility to do so.

We proceed with different scheme, at first we usually try to secure funding of our work for example through the aid of foundations.

We then work on a topic with a team of 2–10 people from Italy and from abroad. When we have finished our work, we publish it, but as we aren't publishers ourselves we have to look for suitable publications and media.

Our strategy is to find various media outlets serving different countries and to publish our work internationally at the same time.

Was there a key moment in your career that made you decide to work as an investigative journalist?

Alessia: Yes, I would say Japan and the Fukushima and tsunami disaster. Japan was my focus even before the Fukushima disaster and I saw then that news coverage as I did it until then is not enough.

It was important for me to investigate the topic more thoroughly and to check what story was hidden behind the daily news. The investigative work helped me to strengthen my interest in Japan, I found more answers to my questions and other possibilities to do my work.

How do you manage to work independently as much as possible and to survive economically at the same time?

Alessia: This is always the big question. IRPI doesn't finance itself through advertising or support from big companies or banks. We are mainly depending on foundations for investigative journalism.

IRPI is currently not fully profitable, so some of us have other, alternative jobs.

But there are stories that we really want to write and although we do not always find initially the necessary funds, we try to keep going anyway.

In recent years, we were lucky because of the positive feedback about work, and we could publish most of our work. And since last year, we have also been contracted to work for foreign media publications. This year we received the first fund from the Open Society.

According to the World Press Freedom Index 2015 from ›Reporters without Borders‹, Italy is on position 73 out of 180 countries. At the same time ›Reporters Without Borders‹ points out a rise in violence, physical attacks and unjustified defamations against journalists in Italy.

How does this assessment relate to your experience?

Alessia: Fortunately we have not experienced this yet. Of course, many of our topics are very sensitive, for example corruption or the Mafia, and we expect every day, that something might happen.

Something else is that freelance journalists and those who do not belong to what many call the elite, referring to regularly employed staff writers, are not paid and their work is not published which is a kind of censorship too.

One can not expect investigative journalism if there is no reward for the work.

Did the so called ›berlusconismo‹ changed the linguistic form of the media?

Alessia: Yes, dramatically. Many people abroad think that only Berlusconi is responsible for the damage done to the media, but for me he is just the tip of the iceberg.

His and other media channels are generally biased, full of infotainment and work of critical journalists. Journalism wasn't much better before, but as a result of the so-called ›berlusconismo‹ many people now think that journalists usually don't work in a truthful and honest way.

But, as I repeat, there are many other obstacles to the freedom of the press in Italy.

One of this is that we don't have a tradition of fact-based journalism, while traditionally we prefer articles based on comments.

How do you manage to maintain a credible journalism in an environment where there are no fixed boundaries between advertising ⁄ PR and news?

Alessia: We have no advertising, that's the difference. So we can work and investigate in all directions.

Are there – against the background of the economical und financial crisis – more journalists in Italy now who submit themselves to self-censorship because they are afraid of damage to their career or losing their job?

Alessia: Yes, absolutely. The number of journalists, who commit self-censorship because they are afraid of losing their jobs, has grown.

According to surveys, the number of freelance journalist raised to 60 percent in Italy and they are not paid or are totally underpaid, that means less than 5000 euros per year.

What future do you see for a free and independent press in Italy?

Alessia: I wouldn't say that I am optimistic but I can see some positive things. There is a group of new and creative people, who are dealing courageously with our system here.

And there are people now, who understand what has previously gone in journalism and what is going wrong in the political system today, especially in the light of the close connection between politics and journalism in Italy. Despite the barriers and difficulties that they face every day, they try to remain independent. So, there is hope.

Which was your biggest scoop until now?

Alessia: The biggest, investigative work of IRPI dealt with the African Mafia.

This work was done by ten journalists (including four IRPI member) over a period of seven months and published in many countries.

Another important story was the case of the Carabinieri policeman from Padua who had raped more than a dozen girls. In a first trial he was sentenced to six years and six months in prison and there are – because of our work – further trials against him.

In the face of all the problems that you, as a journalist, have to fight every day, what drives you to continue your work?

Alessia: (laughs) We are crazy.

We see the results and we notice that our work has a real impact. We are not so much interested to see our names as authors but we are happy about acknowledgments shown from people who respect our work.

This is satisfaction that one can not buy.

<< >>